At A Glance

An intensely passionate work by Rodin that occupied him for many years, originally commissioned in 1880 for a new museum in Paris

Theme derives from Dante’s Inferno (Italian for “hell”), the first part of the epic poem The Divine Comedy

More than 180 figures seem to struggle to free themselves from swirling masses of material

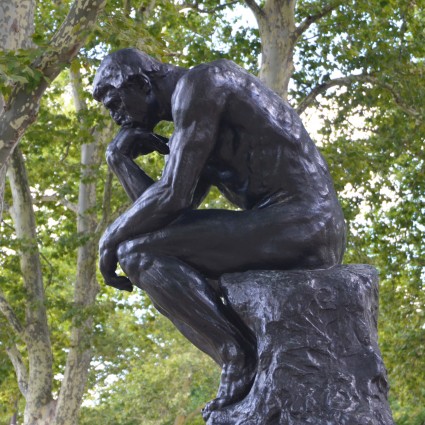

Many of Rodin’s most famous free-standing sculptures began as figures on the gates, including the Three Shades and The Thinker

The gates were never cast in bronze during Rodin’s lifetime

Standing at the entrance to the Rodin Museum in Philadelphia is the first bronze cast of Auguste Rodin’s The Gates of Hell. It was in 1880 that Rodin received the commission for a set of portals for a new Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris that were to be “bas-reliefs representing The Divine Comedy” – a choice of subject that was surely suggested by Rodin himself, as he was an avid reader of Dante.

Writhing in anguish, or unfulfilled desire, the figures on The Gates of Hell – more than 180 of them in all – seem to struggle to free themselves from swirling masses of material. Begun in the year Rodin turned 40, this intensely passionate work occupied him for the next 10 years and at intervals thereafter for the rest of his life. The son of a Parisian civil servant, Rodin attended a government art school but failed three times to gain admittance to the prestigious Ecole des Beaux-Arts. During his long, uproarious career, he was blasted for his audacity, sensuality, and devotion to realism rather than standard notions of beauty. The theme for The Gates of Hell derives from Dante’s Inferno (Italian for “hell”), but Rodin incorporated dozens of figures that have no strict parallel in the poem. For artistic inspiration he drew on Michelangelo’s sculpture and Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise in Florence.

The identifiable borrowings from Dante include the Three Shades, spirits of the dead who stand atop the frame and point to the sufferings below. Directly below them sits The Thinker. About two-thirds of the way down the left door are Count Ugolino and his sons, who endured starvation in a tower until the boys died, which point Ugolino are their flesh. Just beneath these figures are the flowing, straining forms of the famous lovers Paolo and Francesca. In the right-hand door jamb, at the very bottom, kneels a bearded man thought to be Rodin himself, with a small attendant figure that may represent the fruits of his imagination. At the bottom of each door is a tomb, a reminder of the temporal entrance to Hell.

Many of Rodin’s most famous free-standing sculptures began as small figures on the gates or grew out of experiments with the massive project. But the gates themselves were never cast in bronze during Rodin’s lifetime. When Jules Mastbaum decided to establish the Rodin Museum in Philadelphia, he ordered two bronze casts of the gates, one for his museum and the other for the Musée Rodin in Paris. The first cast came to Philadelphia, where architects Paul Cret and Jacques Gréber incorporated it into the design of the museum’s entrance.

Adapted from Public Art in Philadelphia by Penny Balkin Bach (Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 1992) and Sculpture of a City: Philadelphia’s Treasures in Bronze and Stone by the Fairmount Park Art Association (now the Association for Public Art) (Walker Publishing Co., New York, 1974).

This artwork is part of the Along the Benjamin Franklin Parkway tour