At A Glance

Developed as part of the Association for Public Art’s Form and Function program

Pinto’s first permanent outdoor installation in the U.S.

Links the human body with the natural environment

18,000-pound construction made of weathering steel

Fabricated in sections and installed by helicopter

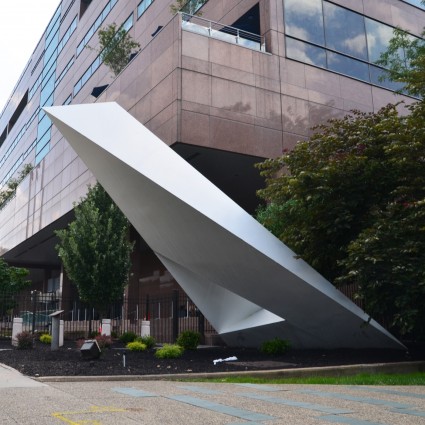

“It’s one of the most breathtaking points along the Wissahickon,” artist Jody Pinto said of the gorge south of Livezey Dam. A span once served to get people across the gorge; when it deteriorated, the Park Commission retro-fitted and installed a staircase from an old ship. To replace the stairs, Pinto designed Fingerspan, an outgrowth of the Fairmount Park Art Association’s (now the Association for Public Art) Form and Function project.

The entire 18,000-pound construction is made of weathering steel that forms a protective coat of rust when exposed to the elements over time.

Pinto, born in New York, grew up in a family of artists and photographers. Many of her works use imagery from the human body. “For me,” she says, “the body is the central source of information, of everything we understand, everything we see.” In Fingerspan, her first permanent outdoor installation in the United States, she wanted to link the human body with the natural environment in such a way that viewers themselves, passing through the work, would help to establish the connection.

The artist considered issues of safety, security, and durability. The steel covering is perforated with 1/2″ holes to prevent people from falling or climbing over the edge, while allowing a view of the spectacular gorge below. The deck is made of steel bar grating and is designed to sustain a load of 100 pounds per square foot. The entire 18,000-pound construction is made of weathering steel that forms a protective coat of rust when exposed to the elements over time. As a reviewer commented, the bridge looks as if it has been in place since the days of the Lenni Lenape Indians.

Samuel Harris of the firm Kieran Timberlake and Harris, who served as architect and engineer for the project, collaborated in developing the concept into a practical structure. The span was fabricated in sections and installed by helicopter. A grant from the Art in Public Places Program of the National Endowment for the Arts supplemented funds from the Association, and the work was donated to the City of Philadelphia.

Adapted from Public Art in Philadelphia by Penny Balkin Bach (Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 1992).

Directions by Car: Park on Allen’s Lane in Mount Airy, and walk down Livezey Lane to the creek at a point where the dam and Canoe Club are visible. Turn left and follow hiking trail (15–20 minutes) to a small steel foot bridge, and climb stone steps to Fingerspan.

Voices heard in the Museum Without Walls: AUDIO program: Jody Pinto is the artist who created Fingerspan. She is a former professor at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and is known for her work in public spaces. She has received awards from the American Institute of Architects and the American Society for Landscape Architects. Diana Gomez is a first grade teacher at Germantown Friends School. She has brought her young students to Fingerspan to experience the joy of passing through the sculpture. Julie Courtney is an independent curator in Philadelphia who has known artist Jody Pinto for over 30 years. | Segment Producer: Bruce Wallace

Museum Without Walls: AUDIO is the Association for Public Art’s award-winning audio program for Philadelphia’s outdoor sculpture. Available for free by phone, mobile app, or online, the program features more than 150 voices from all walks of life – artists, educators, civic leaders, historians, and those with personal connections to the artworks.

RESOURCES

Internationally known for her creative integration of art into architecture and landscape Jody Pinto lives and works in New York City. She has completed nearly forty collaborative projects in the United States, Israel and Japan since 1975. They include a wide range of master-planning, functional elements, landscape interventions, free standing and integrated structural elements. She has received numerous awards and grants including the NEA; Federal Design Achievement Award; National Design for Transportation Award; A.I.A. Honor Award “ Art in Public Spaces “ and two National ASLA Design Honor Awards.

Her drawings are in numerous private and public collections, including the Guggenheim Museum, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Modern Art in New York City; the National Gallery of Art and the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C.; Des Moines Art Center in Iowa; the Denver Art Museum; and the Philadelphia Museum of Art, among others.

A feature article in Landscape Architecture about an award winning project that Pinto collaborated on, describes her basic philosophy of public art: “Pinto, artist on the project, describes designing South Beach (Santa Monica, CA) as an act of ‘peeling back a film, revealing what was already there, and exposing the possibilities. The ‘human theater’ of the beach, the people and their activities, became the central focus of the design. How design can enhance existing uses and inspire new ones became the central question.’ It is rare to find a design that starts from such a humble perspective. The provocative integration of drama and mystery into daily activity provides a connective tissue between life and art.”

Current projects include the design of a street in Harvard Square, Cambridge, MA and a 1000’ cable-stayed pedestrian bridge in Phoenix, AZ.

For more information, visit www.jodypinto.com

To bridge the gap between public art and ordinary life, the Fairmount Park Art Association (now the Association for Public Art) initiated the pioneering program Form and Function in 1980. The Association invited artists to propose public art projects for Philadelphia that would be utilitarian, site-specific, and integral to community life—works that would be integrated into the public context through use as well as placement.

To bridge the gap between public art and ordinary life, the Fairmount Park Art Association (now the Association for Public Art) initiated the pioneering program Form and Function in 1980. The Association invited artists to propose public art projects for Philadelphia that would be utilitarian, site-specific, and integral to community life—works that would be integrated into the public context through use as well as placement.

Each artist was asked to give meaning or identity to a place, to probe for the genius loci, or the “spirit of the place.” The Association for Public Art’s intention was to respond to the needs of a changing city, as well as to accommodate the expressions of individual artists.