The Association for Public Art (aPA) is dedicated to telling the complex stories about public artworks in Philadelphia, and we will be using our platform to actively participate in this essential civic discourse by sharing lesser-known histories and new points of view of sculptures in the coming months. Some of these stories are disturbing, and some are inspiring.

A monument to the “unselfish devotion to duty” of African American military men was a rare objective in early 20th century America; the artist began his work, but the struggle to realize the memorial had just begun.

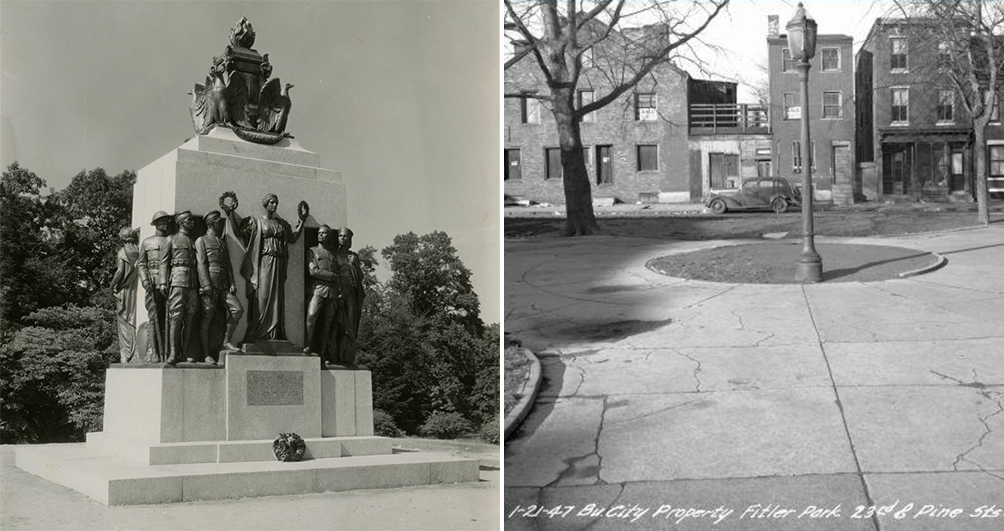

The story behind Philadelphia’s All Wars Memorial to Colored Soldiers and Sailors (1934) by artist J. Otto Schweizer is a significant one that our organization never gets tired of sharing. When the sculpture was first brought to the attention of the Association for Public Art (aPA), it was in poor condition and sited in a remote location in West Fairmount Park. However, a large wreath at the site was a clue that Black veterans and those paying tribute had been gathering at the memorial for Veterans Day, no doubt for years. The aPA arranged for initial conservation treatment in 1984, and the humanity of the monument was immediately stirring. Revealing its dignified beauty and telling the story of the clearly racist attitudes that placed it at the site, energized fiercely determined community leaders who formed a Committee to Restore and Relocate the All Wars Memorial. The history of this memorial and the racism that lies at the heart of its long journey should be revisited at this time, when we strive toward racial justice and reflect on monuments across the nation.

A GRAY INVINCIBLE (Commissioning a Monument to Black Military Men)

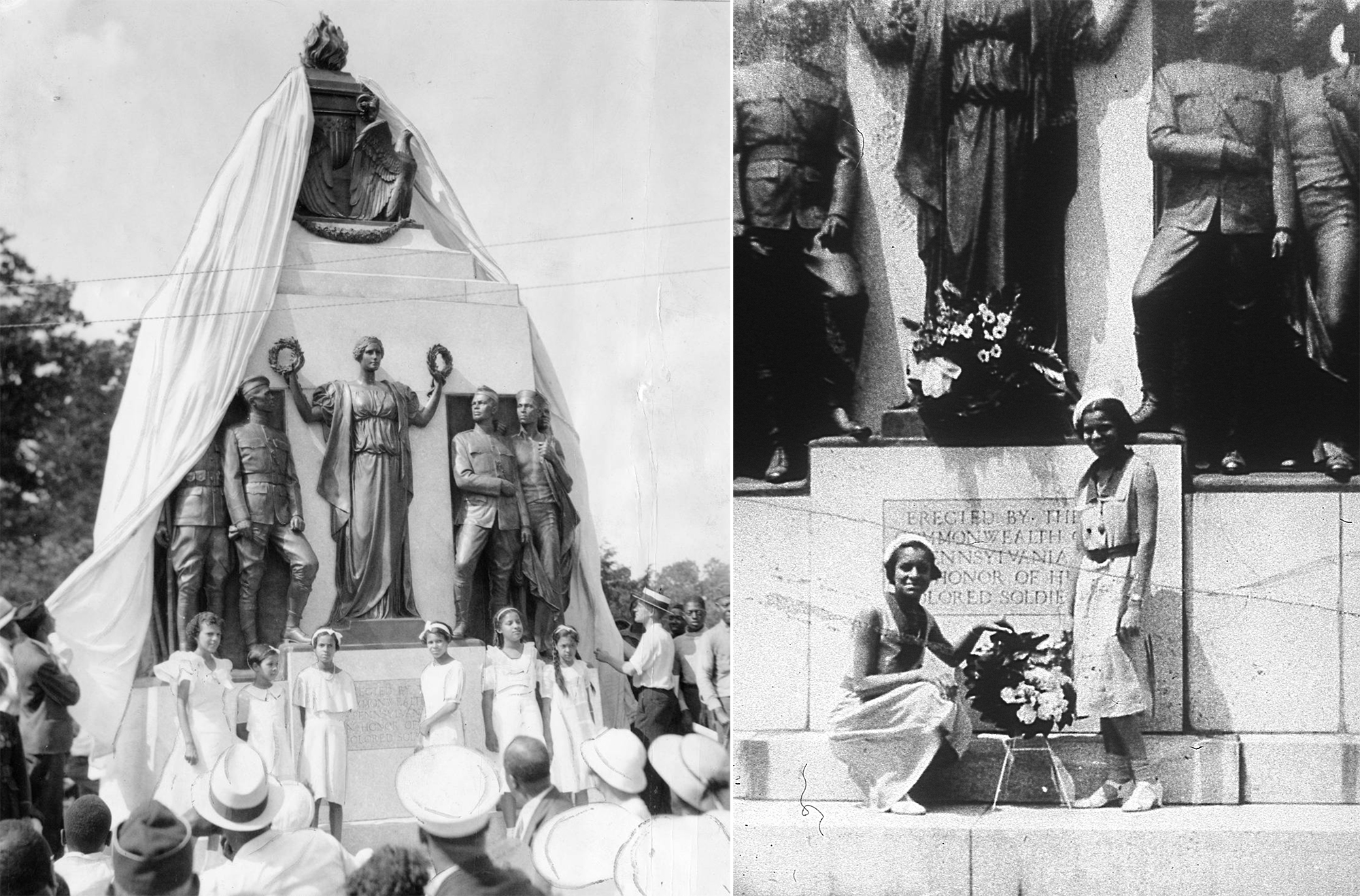

The idea for the All Wars Memorial began in the 1920s, when the Honorable Samuel Beecher Hart, an African American Pennsylvania legislator and captain of the Gray Invincibles – the last “colored” unit in the Pennsylvania Militia – sponsored a bill to have a memorial created to honor the state’s Black military men who had served the U.S. in wartime. Funds were finally appropriated in 1927, and a Colored Soldiers Statue Commission was created by the Governor. His five appointees to the Commission were African American. A competition was held, and Philadelphia sculptor J. Otto Schweizer was selected. The Swiss-born immigrant, who lived and worked in the city’s Tioga neighborhood, is responsible for many other historic monuments commissioned for sites in Pennsylvania. Samuel Beecher Hart wanted the memorial, which is now owned by the City of Philadelphia, to be in a prominent location, and the artist recommended the Parkway. A monument to the “unselfish devotion to duty” of African American military men was a rare objective in early 20th century America; the artist began his work, but the struggle to realize the memorial had just begun.

A BIASED ART JURY

When the All Wars Memorial was brought before the city’s powerful Art Jury – the forerunner of what is now the Art Commission – for approval, it was denied its proposed location on the Parkway due to blatant racism. According to the Associated Press, the Art Jury’s reasoning was that the Parkway was becoming an avenue of war memorials that were “mediocre.” Fitler Square was proposed as an alternative, but public protest against that placement mounted, with one nearby building owner writing to the Art Jury in opposition, claiming that it had “very desirable tenants living in these apartments, and we feel that such a statue opposite the apartments would cause us a loss of tenancy.” Fitler Square was the epitome of urban blight in the 1930s. It made little sense as a location, as the area was largely inhabited by Irish-Americans who had no interest in the memorial – and the Black community saw the site as unworthy. The racist intention behind keeping the All Wars Memorial off of the Parkway was transparent: keep the monument to Black sacrifice out of sight. A compromise eventually was reached to place the memorial in West Fairmount Park.

A REMOTE LOCATION and THE PEOPLE’S FIGHT

After heated debate, city officials compromised on a site in West Fairmount Park, and the All Wars Memorial was installed in what was then a remote area of West Fairmount Park behind Memorial Hall (now the Please Touch Museum), where it languished and remained hidden for 60 years. Samuel Beecher Hart’s granddaughter, Doris Jones Holliday, tried for years to have the memorial relocated. “Doris fought with the city, and she wrote letters, made phone calls, and talked to people about moving the statue to a better place,” said Hart’s great-grandson, Samuel Hart Jones, Jr., who would visit the statue in Fairmount Park as a boy with his aunts Doris and Harriet and his grandmother.

It was finally relocated to the Parkway in 1994 thanks to the efforts of the Committee to Restore and Relocate the All Wars Memorial, led by Michael Roepel. “In 1993 I was a city planner, and it was brought to my attention by the [Association for Public Art] that there was a monument located in the park made up of African American soldiers,” said Roepel. “You practically had to be lost to find out that the memorial existed.” He helped form a committee to restore and relocate the monument to “its rightful place on the Parkway.”

WHO WERE THEY?

“The models were people that the artist knew, and I think that is just one of the reasons why they are so imposing. Their posture is noble and dignified, and their faces are intense and exquisitely composed,” said Penny Bach, Executive Director of the Association for Public Art. The six black soldiers and sailors flank a woman representing Justice, who was modeled after the artist’s wife. Above them is a symbolic “torch of life” surrounded by four American eagles, and allegorical figures on the other side of the monument represent the principles for which American wars have been fought. While the monument is not without its issues – there is the conspicuous detail of the towering allegorical white female flanked by Black military men – it is overall an exceptional work of sculpture that is appreciated and beloved by many.

FINALLY, ON THE PARKWAY AT LAST

In 1994 the All Wars Memorial to Colored Soldiers and Sailors was relocated by the City of Philadelphia with appropriate fanfare, and it has stood proudly at a prominent location on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway in Logan Square. Doris Jones Holliday, who lobbied for its move and as an 11-year-old child pulled the drape off of the sculpture in 1934, asked her nephew to represent the family and remove the drape 60 years later. Also attending were the artist’s granddaughters, Elyssa S. Burke and Carol Sides, who remembered playing at Schweizer’s feet in his studio.