Pictured above: Detail of Joseph Goebbels viewing the Degenerate Art Exhibition. Full photo below. Photo © Gerhard-Marcks-Stiftung, Bremen.

An Essay by Dr. Paul B. Jaskot

Dr. Paul B. Jaskot is Professor of Art, Art History and Visual Studies at Duke University. His scholarly work focuses on the political history of Nazi art and architecture as well as its postwar cultural impact. This essay is presented as part of the Association for Public Art’s recent installation of Gerhard Marcks’ Maja sculpture in a new public park in Philadelphia.

It is shocking to remember that one of the most popular blockbuster exhibitions of all time has been the racist and reactionary “Degenerate Art” show. The exhibition opened in 1937 in Munich under Nazi Party patronage and featured two works by Gerhard Marcks. By the time the show returned to Joseph Goebbels’ Propaganda Ministry in 1941 after touring cities in Germany and Austria, over 3 million people had visited. Needless to say, “degenerate” was a term already familiar to readers of German art criticism before the exhibition, as it had been applied by many Nazi artworld figures to various artworks and artists representing supposedly unhealthy, Communist, and/or Jewish culture. This definition included artists like Marcks, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, and others interested in Expressionist tendencies to distort depictions of the body for critical effect.

[Maja] points to the long history behind Marcks’ persecution – his career as a teacher of sculpture at the Bauhaus and elsewhere, as well as his Expressionist tendencies – but also to his withdrawal from more controversial subjects, radical forms, or public acts that could have overtly endangered him and his family.

On the surface of things, Nazi art policy as embodied in the “Degenerate Art” exhibition seems to be straightforward. On the one hand, modernist artists like Marcks who experimented with form and subject matter were “bad” artists. They dragged down German culture with their depictions of sexualized bodies, ambiguous takes on Christian themes, or overt sarcastic responses to the military and to the state. On the other, were the “good” artists at the state-sponsored “Great German Art Exhibition” that opened in Munich the day before “Degenerate Art.” Those latter artists – with their heroic landscapes, naturalistic nudes, and portraits of Hitler – featured leading figures like the sculptor Arno Breker, who were collected by Hitler and other Nazi officials.

And yet, the matter was never so clear in Nazi Germany. There was never a consistent definition of what defined “degenerate” or, conversely, who, beyond a few privileged artists like Breker, was a “true” Nazi artist. Instead, artistic positions varied and opinions changed strategically. So, for example, the hated Bauhaus art school where Marcks taught from 1919-1925 was damned as a hotbed of Marxist culture in the Nazi Party newspaper in the early 1930s as the party was trying to come to power; but after 1933 when the party came to power and the school closed, hardly a peep was uttered about it in the official art press. In the “Degenerate Art” show itself, many former professors of the Bauhaus were featured, including Marcks, Paul Klee, and Wassily Kandinsky. But in all the 650 works shown only one wall text referred to the Bauhaus and that was to a work by the Russian-born Kandinsky in order to make the point of his supposedly “Bolshevist” leanings. By 1937, an artist’s affiliation to the Bauhaus wasn’t that important; what was important was whether such affiliation could successfully be instrumentalized into a propaganda of hate, especially against Jews and (Russian) Communists. Even there, though, Nazi officials were hardly consistent; in the entire show, only one artist was actually the enemy they most despised, a Jewish Communist. Not surprisingly, they put that artist – Otto Freundlich – on the cover of the catalog.

Marcks existed within a spectrum of “degeneracy” that was neither ideologically or politically consistent, including from the point of the view of the artists as well. Some artists like Freundlich were committed anti-fascists. Ultimately, he would pay for both his ethnicity and politics; after the fall of France in 1940, he was arrested and deported to the concentration camp of Majdanek where he was murdered. It is worth noting, however, that no artists (including Freundlich, who worked with Expressionist and abstract forms) were ever killed solely because of the modern style of their work. Instead, arrests were made because of their perceived “racial” background or their political affiliations and beliefs.

Other artists, including those labeled as “degenerate,” could still continue in one way or the other through choosing to be more neutral in their content or more traditional in their form. For example, Walter Gropius and Mies van der Rohe, the first and last directors of the Bauhaus, make the point; they seemed to be personas non grata when the Nazis came to power in 1933, and yet only one year later they both did installations for the state-sponsored “German Volk—German Work” exhibition. In this regard, Gropius’ appointment at Harvard and Mies’ at Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago in the late 1930s are more accurately described as career moves rather than signs of their “exile” or a critical attitude toward the Nazi state.

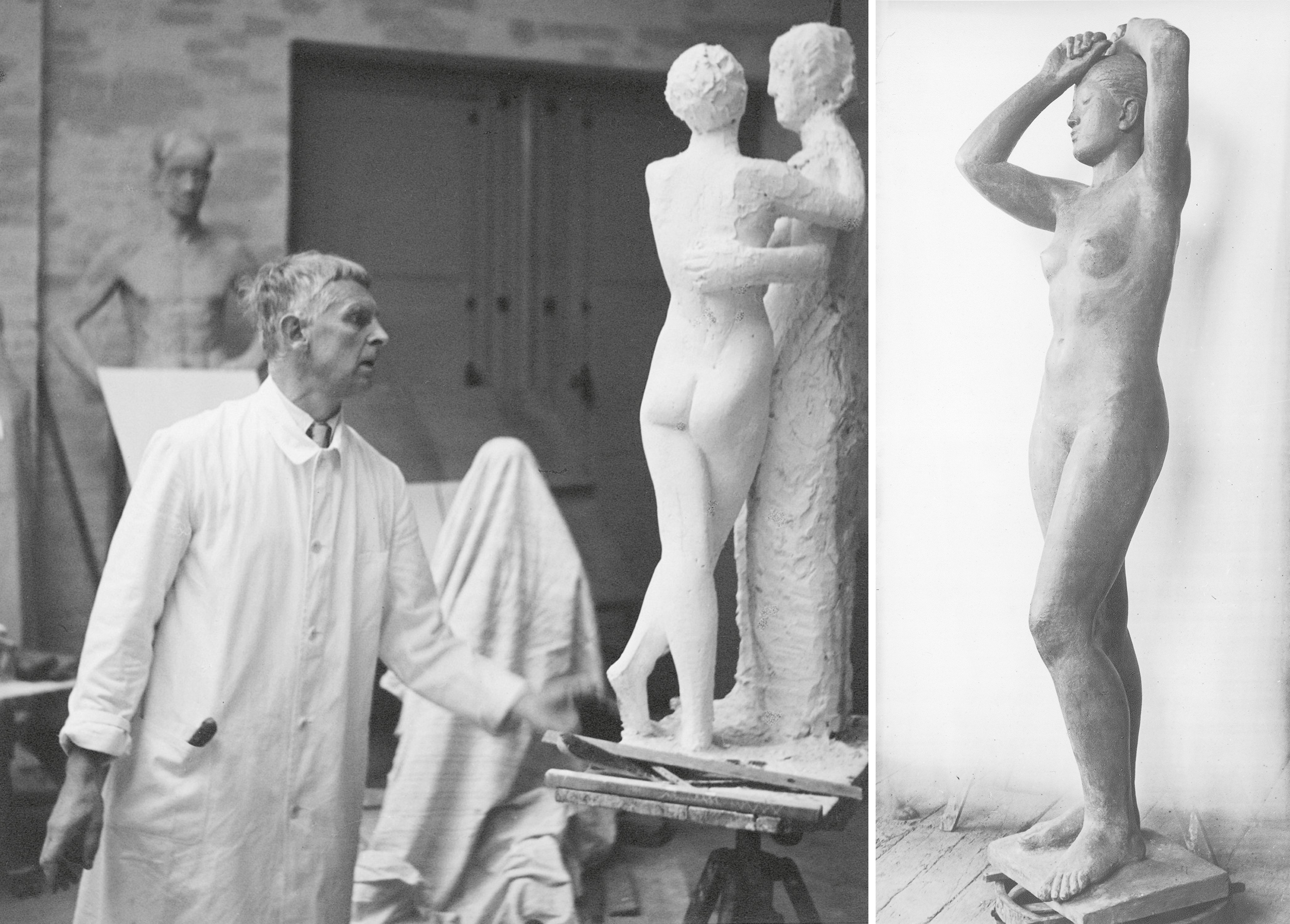

Understanding such inconsistency is important context for Gerhard Marcks. Marcks was neither ethnically Jewish nor Marxist in his views, and his relationship to the Nazi state varied. Certainly his biography clearly evidences the attacks on his career by the state. Marcks stayed in “inner immigration” in Germany after he was dismissed from his teaching position in 1933 for defending a Jewish colleague. He was further pilloried when his two works were featured in the “Degenerate Art” show. In that same year, one of his works (Joseph and Mary) from the Dresden state collection was sold off unceremoniously for a little over the equivalent of $110 along with many other state-owned works in the Galerie Fischer auction in Lucerne. Marcks remained mostly hidden from the public, befriending other artists in inner immigration like Ernst Barlach and Käthe Kollwitz.

And yet, at the same time, Marcks did not completely disappear. A long and favorable essay by Carl Linfert was written about him in 1935 in the Berlin literary publication Neue Deutsche Rundschau. A few of his works were shown by Karl Buchholz in his gallery in Berlin, although a planned show of his work there in 1937 was forbidden to open after the “Degenerate Art” exhibition. In general, he had few opportunities to show his work during the Nazi period but, at the same time, managed to continue to produce, including working in bronze – not insignificant given the restrictions on metals during the war. His politics were not in the least anti-state and, indeed, his son died in 1943 defending the German war effort on the Russian front.

This history in no way belittles the real restrictions and critical attacks he faced during the Nazi period. But it does place him in the spectrum of the more moderate and cautious group of artists who rarely, if ever, consistently or overtly confronted the intensifying Nazi racism and anti-Marxism. Such a position allowed him to live out the war in Germany with the help of friends and supporters. Maja (1942), a sculpture that is both conventional in its subject and modestly modernist in its slight distortions of the body, reveals this context and this inconsistency. It both points to the long history behind Marcks’ persecution – his career as a teacher of sculpture at the Bauhaus and elsewhere, as well as his Expressionist tendencies – but also to his withdrawal from more controversial subjects, radical forms, or public acts that could have overtly endangered him and his family. In this regard, the sculpture reveals the very real and difficult choices made by any citizen in Nazi Germany confronted by powerful conditions of growing authoritarianism and increasing oppression.

PAUL B. JASKOT is professor of art history at Duke University and the Director of the Wired! Lab for Digital Art History & Visual Culture. This year (2021-2022), he is the Ina Levine Invitational Scholar, at the Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. His work focuses on the relationship between architecture and politics in modern Germany, with a specific emphasis on the National Socialist period. He is the author, editor, and co-author of multiple articles and books on this topic including, most recently, The Nazi Perpetrator: Postwar German Art and the Politics of the Right (2012) as author and New Approaches to an Integrated History of the Holocaust: Social History, Representation, Theory (2018) as co-editor. In addition, Jaskot is a founding member of the Holocaust Geography Collaborative, an international collective of scholars working on how digital mapping and other computational methods help us to advance questions concerning the genocide of the European Jews. Jaskot’s digital art history work has appeared in the Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians and Historical Geography, among other venues. In addition to his scholarly work, he is an active advocate for digital art history, its evaluation, and promotion as well as other issues related to sustaining the international development of art history through his continued activity with the College Art Association (CAA), the largest professional group for academic artists and art historians in the United States. From 2008-2010, Jaskot served as President of the CAA. Jaskot was the 2014-2016 Andrew W. Mellon Professor at the Center for the Advanced Study of the Visual Arts at the National Gallery of Art (Washington, DC). He co-directed the Kress-sponsored Summer Institute on Digital Mapping and Art History (2014).

PAUL B. JASKOT is professor of art history at Duke University and the Director of the Wired! Lab for Digital Art History & Visual Culture. This year (2021-2022), he is the Ina Levine Invitational Scholar, at the Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. His work focuses on the relationship between architecture and politics in modern Germany, with a specific emphasis on the National Socialist period. He is the author, editor, and co-author of multiple articles and books on this topic including, most recently, The Nazi Perpetrator: Postwar German Art and the Politics of the Right (2012) as author and New Approaches to an Integrated History of the Holocaust: Social History, Representation, Theory (2018) as co-editor. In addition, Jaskot is a founding member of the Holocaust Geography Collaborative, an international collective of scholars working on how digital mapping and other computational methods help us to advance questions concerning the genocide of the European Jews. Jaskot’s digital art history work has appeared in the Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians and Historical Geography, among other venues. In addition to his scholarly work, he is an active advocate for digital art history, its evaluation, and promotion as well as other issues related to sustaining the international development of art history through his continued activity with the College Art Association (CAA), the largest professional group for academic artists and art historians in the United States. From 2008-2010, Jaskot served as President of the CAA. Jaskot was the 2014-2016 Andrew W. Mellon Professor at the Center for the Advanced Study of the Visual Arts at the National Gallery of Art (Washington, DC). He co-directed the Kress-sponsored Summer Institute on Digital Mapping and Art History (2014).

Related Presentations:

DR. ARIE HARTOG is Director of the Gerhard-Marcks-Haus in Bremen, Germany, a museum for modern and contemporary sculpture inspired by the work of Gerhard Marcks (1889-1981). His presentation provides an in-depth look at the German artist’s struggles before and during WWII, the creation of Maja, and its survival from Nazi destruction.

PENNY BALKIN BACH is Executive Director & Chief Curator of the Association for Public Art. She is known for her work with artists and innovative approaches to connecting public art with its audiences. Bach shares the fascinating story behind Maja’s debut in Philadelphia more than 70 years ago.