Association for Public Art (aPA) Executive Director Penny Balkin Bach recently took the opportunity to write for ARTSblog about the little known origins of public art in Philadelphia with “Our Shared Public Art (and Placemaking) Legacy”. She discusses the early innovators and civic-minded people who founded and supported our organization (formerly the Fairmount Park Art Association) and established the earliest percent for art programs in the United States. Read the full post on ARTSblog or below.

Our Shared Public Art (and Placemaking) Legacy

by Penny Balkin Bach

At the Americans for the Arts 2015 Annual Convention, I was honored to accept the 2015 Public Art Network Award on behalf of the Association for Public Art (aPA) and also the early innovators who guide our work today. I am acutely aware that as the nation’s first non-profit public art organization, aPA has a unique 140+ year legacy. While we do not operate in the same environment as government agencies, I believe that recognizing our shared public art legacy can fortify our position by imparting clarity, credibility, and clout.

So who were those civic-minded people who founded and supported the Fairmount Park Art Association (now the Association for Public Art) and established the earliest percent for art programs in the United States?

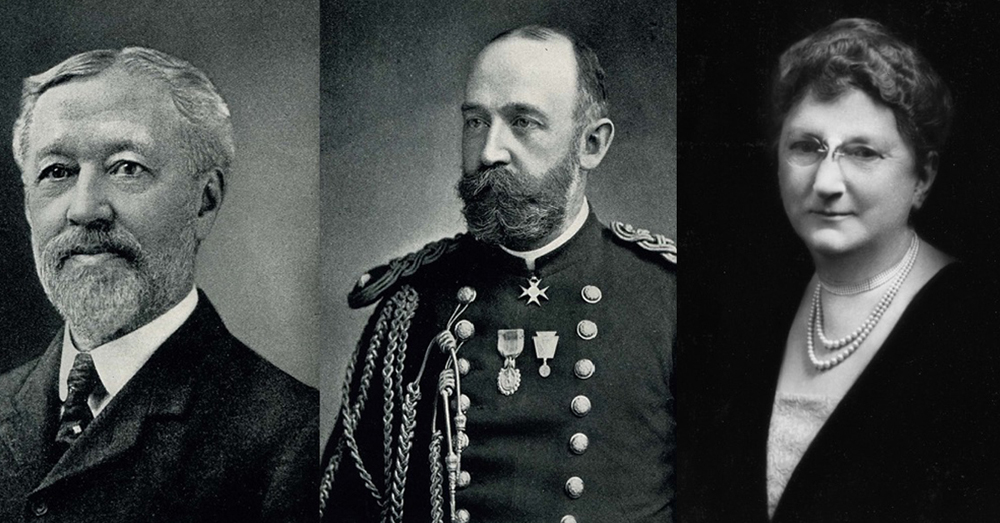

Founded in 1872, the aPA was from its inception dedicated to the integration of art and urban planning. This was a citizen’s movement and a membership organization, not a governmental program, a distinction that holds to this day. In their early 20s, founders Henry Fox and Charles Howell enticed a group of pioneering trustees and subscribers from all walks of life—merchants, entrepreneurs, lawyers, arts professionals and collectors— to support their new organization.

They held the common belief that placing works of art in public spaces would enable people of all classes to share equally in a public trust. Somewhat familiar? The aPA became the beneficiary to public-spirited Ellen Phillips Samuel’s residuary estate following her death in 1913. Although she could not serve on the all-male Board, Samuel was an active member of the Fairmount Park Art Association and a philanthropic supporter of many local cultural activities. Her bequeath was said to be one of the largest bequests of its kind in the country at the time. Samuel left us two rather extraordinary directives: first, to spend only the interest on the endowment, not the principal. Second, she asked that the aPA put advertisements in international newspapers to attract for exhibition the work of a wide range of artists who might be commissioned to create new sculptures for Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park. What thoughtful and expansive foresight!

Few people know that an artists’ movement in Philadelphia instigated the first two percent for art programs in the United States in 1959. In 1957, the local chapter of Artists Equity asked their lawyer Raymond Speiser, himself an art collector, to help establish a percent for art program for private development. Speiser called upon his friend, the architect Louis Kahn, to join him in this mission to invite Michael von Moschzisker, a writer and then Chairman of Philadelphia’s Redevelopment Authority, to cocktails at the Philadelphia College of Art.

Over cocktails, Speiser and Kahn convinced him of the merits of setting aside funds for fine arts on redeveloped properties. In 1958, von Moschzisker pleaded his case to the National Conference of Editorial Writers, where the idea gained national exposure; and in 1959, the Redevelopment Authority’s percent for art requirement went into effect. Simultaneously, Benton Spruance, a printmaker and President of Artists’ Equity, and his sculptor friend Joseph Greenberg approached Henry W. Sawyer III, a lawyer, City Councilman and civil rights crusader, who was also on the Board of the aPA. All of these protagonists knew one another, as you might imagine.

Evidently Sawyer had tried for some time without success to introduce percent for art legislation in City Council. Finally, just as Sawyer was about to finish his last term in office, the City Council surprised him and passed his ordinance. He told me, “I always thought of it as my going-away present.” So behind this movement were: a printmaker and head of Artists’ Equity, a sculptor, an architect, a redeveloper, a lawyer and collector, and an aPA Trustee and City Councilman. What a great lesson in how to get something to stick in city government.

My personal inspiration comes from the artist Marcel Duchamp. He believed that the audience completes a work of art, which I believe to be a tenet of public art. At his 1957 lecture “The Creative Act,” Duchamp famously stated that “the creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world . . . and thus adds his own contribution to the creative act.” This proclamation was issued during the period when he was secretly creating his final work, Etant Donnés, now installed in the Philadelphia Museum of Art – a work that can only be viewed by looking into a peephole, for lack of a better word, thus completing the work of art as well as creating a sense of intimate complicity.