The Monumental Tour sculpture exhibition is on view in Philadelphia through January 30, 2022. In partnership with the presenters, Kindred Arts and Philadelphia Parks & Recreation, the Association for Public Art highlights nearby sculptures in the city that relate to these nationally-touring works.

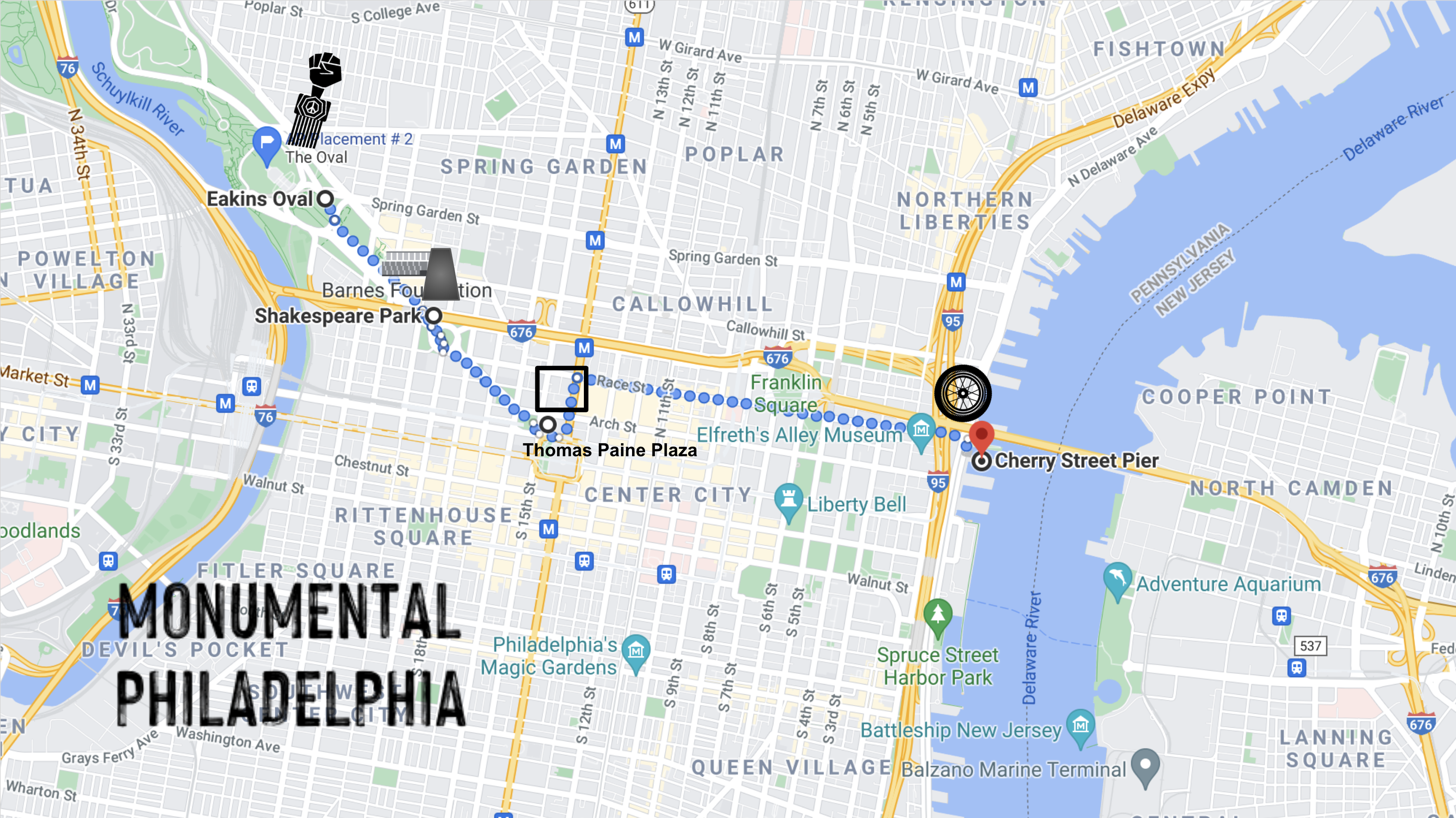

Monumental Tour is a touring group exhibition of sculptures by acclaimed American artists ARTHUR JAFA, HANK WILLIS THOMAS, CHRISTOPHER MYERS, and COBY KENNEDY that “honor and examine aspects of the African American experience, from the first slaves brought over in the 16th century to the present-day prison pipeline, and the struggle for liberation in between,” explains Marsha Reid, Director and Curator of Kindred Arts. The sculptures have been installed at four carefully considered public sites across Center City: Eakins Oval, Shakespeare Park, Thomas Paine Plaza, and Cherry Street Pier. Philadelphia’s iteration of Monumental Tour is supported by the City of Philadelphia and the Delaware River Waterfront Corporation.

Reid continues, “Individually, the sculptures invite the viewer to consider: colonization, oppression, privilege, Black middle-class labor, and the decline of industry, Black pride, Black power, Black joy, and subjugation. Each work is an invitation to viewers from any background to learn about and connect with a narrative or era they may not have endured personally, but which continues to impact the African American experience.” monumentaltour.org #MONUMENTALTOUR #monumentalPHILADELPHIA

Connections with Nearby Sculptures in Philadelphia

Monumental Tour uniquely highlights the African American experience in the United States and inspires closer attention to nearby permanent sculptures in Philadelphia. These permanent public sculptures can be seen through a new lens, inviting a critical eye, and providing an opportunity to discover (or rediscover) public art within the context of the Monumental Tour works that Kindred Arts has insightfully placed throughout Philadelphia.

Monumental Tour: All Power to All People by Hank Willis Thomas

Related nearby: Joan of Arc by Emmanuel Frémiet

Eakins Oval and Pennsylvania Ave

A fist raised high to the sky is an immediate visual connection between All Power to All People and Joan of Arc. This bold gesture conveys a sense of power, strength, determination, and fearlessness. It tells us that these figures are taking a stand or fighting for something important, urgent, and risk-taking, in a way that emphasizes peace and unity (see the peace symbol in the Afro pick).

The Afro pick and Joan of Arc are also widely-recognized symbols of cultural identities: one for Black power and pride, and the other for French political and social change.

For Hank Willis Thomas’s All Power to All People, the Afro pick holds multiple meanings and represents different things to different people – an era, a sound, a counter culture. It’s a symbol of community, strength, perseverance, comradeship, equal justice and belonging. It’s a uniting motif, worn as adornment, a political emblem and signature of collective identity.

The image of Joan of Arc similarly holds many associations beyond French heritage. She’s become a symbol of feminism and female power, sainthood and martyrdom. It’s also worth noting that Philadelphia’s Joan of Arc (1890) was the first monument to a historic female figure installed in Philadelphia. It was commissioned by the Fairmount Park Art Association (now the Association for Public Art) with Philadelphia’s French community to commemorate their centennial, the anniversary of the fall of the Bastille and the launch of the French Revolution.

Monumental Tour: Caliban’s Hands by Christopher Myers

Related Nearby: Shakespeare Memorial by Alexander Stirling Calder

Shakespeare Park

The connection between the Shakespeare Memorial and Caliban’s Hands is straightforward: Caliban was a character from Shakespeare’s The Tempest, and the sculpture is installed near the memorial in Shakespeare Park in front of the Free Library.

Caliban was half human, half monster and forced into servitude. Many consider The Tempest an allegory of European colonization, and Caliban’s character has featured prominently in arguments that defend or resist colonialist tyranny. Christopher Myers’ Caliban’s Hands, according to the artist, is symbolic of the indigenous lands and cultures occupied and suppressed by European colonial societies, and speaks to the dynamics of privilege, oppression, and forced servitude.

Looking up at the Shakespeare Memorial, we see the knife in Hamlet’s hands representing Tragedy, and the rolling laughter of the jester beside him representing Comedy. A theme emerges about life and death – maybe something sinister – that can relate to Caliban’s fate. Engraved on the memorial is the famous Shakespearean quote, “All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women are merely players” from the Seven Ages of Man, a monologue about the stages of life from infancy to death. We might consider that Caliban is merely a player on life’s cruel stage.

The sculptor who created the Shakespeare Memorial is Alexander Stirling Calder, father of Alexander “Sandy” Calder, known for his mobiles. The memorial was commissioned by the Fairmount Park Art Association (now the Association for Public Art) with the Shakespeare Memorial Committee and installed on Shakespeare’s birthday in 1929.

Monumental Tour: Kalief Browder: The Box by Coby Kennedy

Related Nearby: Government of the People by Jacques Lipchitz

Thomas Paine Plaza

Installed in front of the Municipal Services Building in Thomas Paine Plaza, these two sculptures stand in contrast to one another: one is a celebration of our government and democratic systems, while the other takes critical aim at its institutions and policies.

Kalief Browder: The Box by Coby Kennedy is a protest work casting light on the U.S. carceral system and how civil liberties are abused. The steel and glass sculpture, which is illuminated at night, replicates the exact dimensions of a solitary confinement cell – six by eight by ten feet – specifically paying tribute to Kalief Browder, who was incarcerated for three years without a trial. The Box makes painfully real the solitude and inhumanity of these conditions.

Nearby is Jacques Lipchitz’ Government of the People (1976), commissioned by the City of Philadelphia with assistance from the Fairmount Park Art Association (now the Association for Public Art). A massive bronze sculpture, it stands as a symbol of the aspiration for democracy. The stacked bodies struggle, but together they succeed through mutual dedication, strength and support. The striving is a far cry from the isolation and emptiness of The Box below.

There is a deeper conversation between the works, given the history of the location. The Municipal Services Building plaza has been a frequent place of protest for injustices of all sorts. It’s also where the controversial statue of former Mayor Frank Rizzo was removed in 2020 during the Black Lives Matter uprisings. Rizzo was known for his racism, bigotry and police brutality, and the removal came after years of calls to have it taken down.

Monumental Tour: Big Wheel IV by Arthur Jafa

Related Nearby: The President’s House by Emanuel Kelly and Kelly/Maiello Architects, Lorene Cary, and Louis Massiah

Cherry Street Pier and Independence Mall

These two installations are separated by some distance – about a mile walk down Market Street – but they are both powerful evocations of Black experience through the vision of African American artists.

Arthur Jafa’s Big Wheel IV is a contemporary work that reflects the decline of the Black middle class in Mississippi, where the artist spent his childhood. A large monster truck tire is wrapped in a mesh of iron chain. At the center is an abstract medallion that is 3D printed from melted chains. It is an “industrial chakra” that calls to mind the deindustrialization that the artist and his generation saw hurt the Black middle class. Notably, this sculpture was exhibited at the 2019 Venice Biennale.

The President’s House (2010) by Emanuel Kelly and Kelly/Maiello Architects, Lorene Cary, and Louis Massiah marks the home where Presidents George Washington and John Adams lived. The installation recreates the home as an open-air brick structure and pays homage to the nine documented enslaved persons of African descent who were part of Washington’s household. A glass vitrine overlooks structural remains uncovered during an archeological dig; bronze footprints symbolize the road to freedom; and etched are tribal names and places of origin of the millions of Africans who were brought to the U.S., as well as the names of those nine enslaved individuals.

Both installations use multimedia components to create gripping narratives. For Big Wheel IV, a looping song fills the Cherry Street Pier space through speakers in the floors, and at The President’s House, motion-activated video screens tell the stories of those enslaved persons who lived there.