Maja

Maja (1942, cast 1947) is now on view in "Maja Park", on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway at 22nd Street, Philadelphia, PA

- Philadelphia Inquirer: One of city’s landmark works of public art is coming out of storage and into its own park

- Hidden City: A Symbol of Survival and Hope Returns to the Parkway

- Learn about the conservation of Maja here

- Read about “Gerhard Marcks and the Nazi Concept of ‘Degenerate Art’” here

- Visit the Gerhard Marcks Museum in Bremen, Germany here

Back on the Parkway decades later in new public park

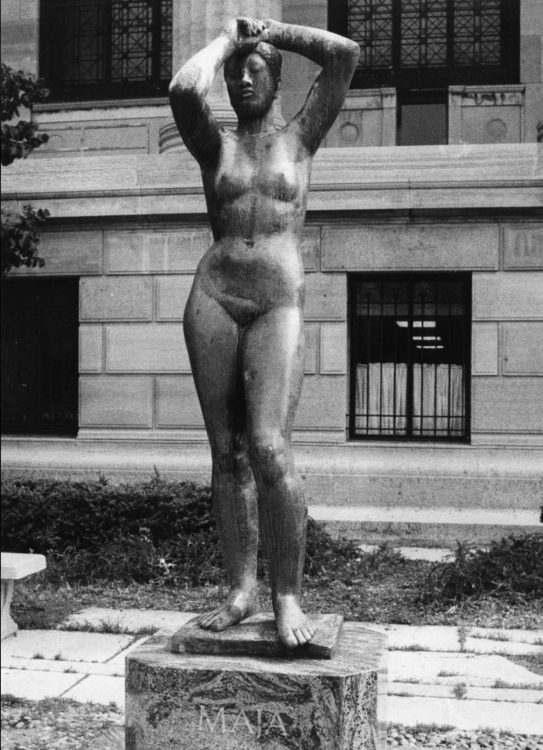

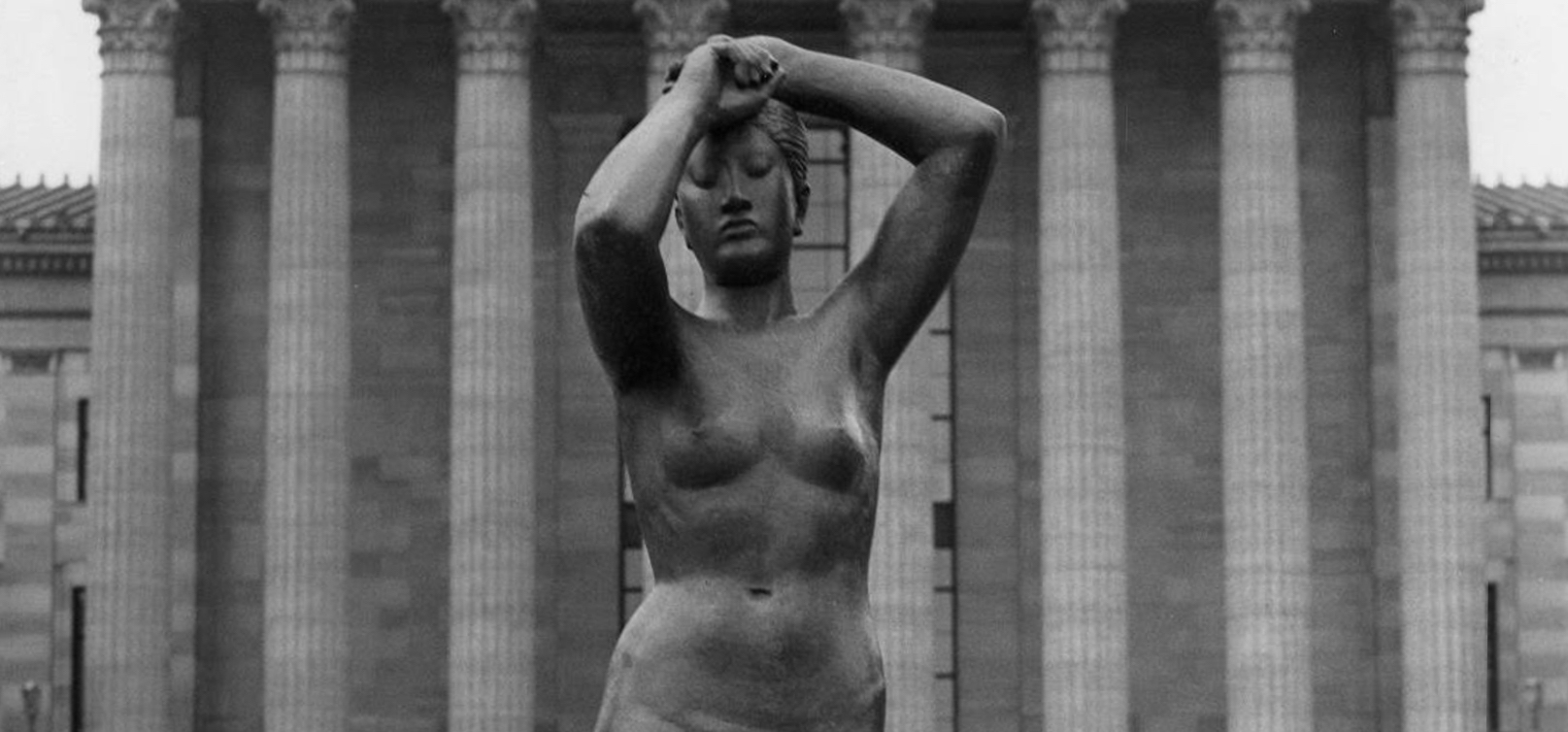

After spending more than 25 years out of public view, Gerhard Marcks’ bronze Maja sculpture (pronounced \MAI-uh\) was installed in March 2021 in a new public park – named Maja Park – on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway at 22nd Street. The Association for Public Art (aPA), which purchased Maja in 1949, had been waiting for the right opportunity and appropriate site to reinstall the sculpture, which once stood atop the steps of the nearby Philadelphia Museum of Art for decades. The development of Maja Park, designed by Ground Reconsidered, has been a private/public partnership between AIR Communities, which owns the adjacent Park Towne Place Museum District Residences, and Philadelphia Parks & Recreation, with support from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

Press Release: Gerhard Marcks’ Maja Sculpture Returns to the Parkway ››

Debut at the Association’s 1949 Sculpture International Exhibition

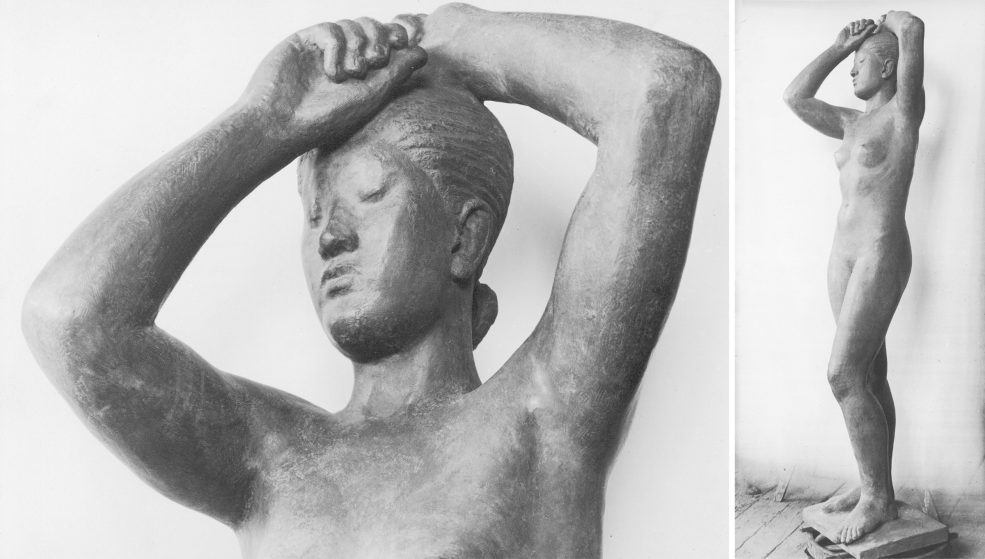

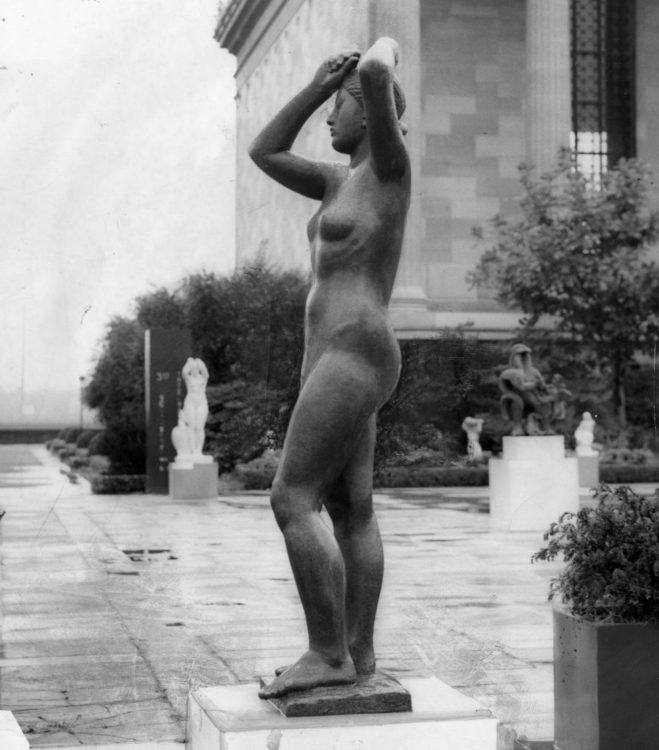

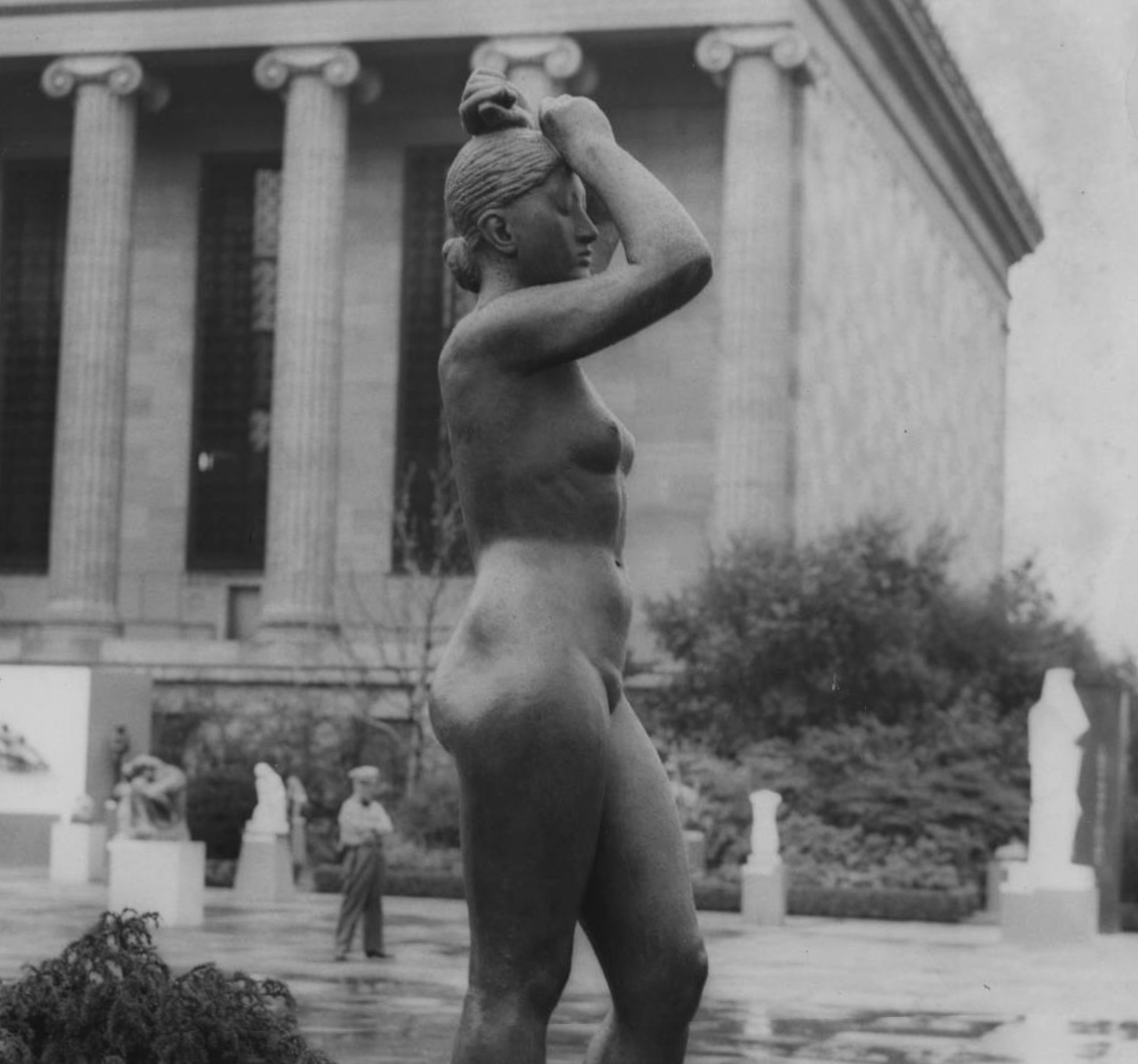

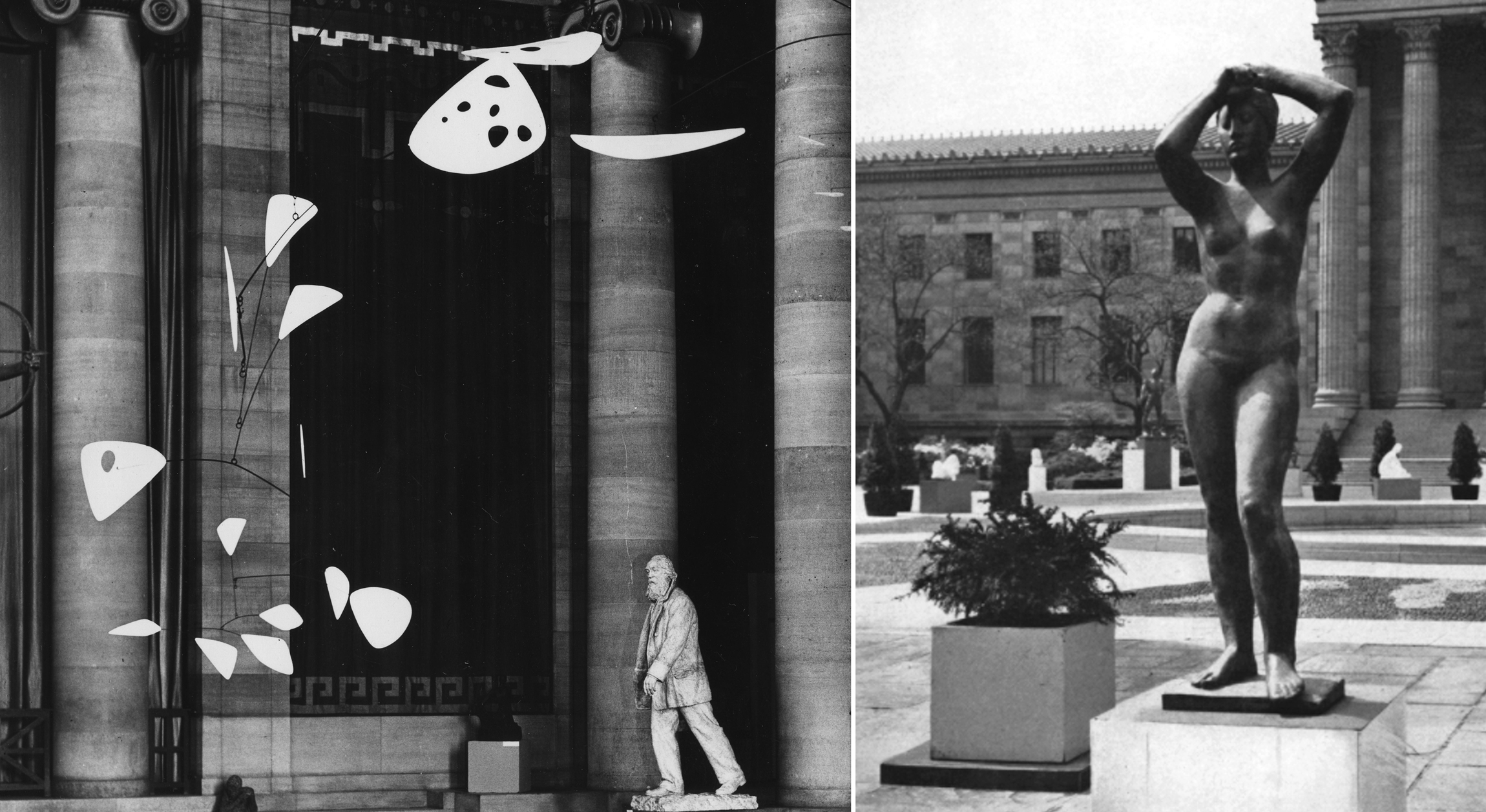

Maja first enjoyed the limelight in Philadelphia in 1949 at the Association for Public Art’s Third Sculpture International Exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where the sculpture was exhibited prominently at the top of the Museum’s steps. This series of sculpture exhibitions in 1933, 1940, and 1949 featured works by hundreds of sculptors from around the world, and was organized by the Association to introduce the public to contemporary sculpture and to identify artists for the Ellen Phillips Samuel Memorial on Kelly Drive. The Association also purchased a number of sculptures from these exhibitions, including Maja. Created in 1942 and cast in 1947, Maja was considered a particularly significant sculpture in the third exhibition, which also included works by Alexander Calder, Jacques Lipchitz, Pablo Picasso, and Barbara Hepworth. It was widely seen by sculptors and critics as one of the most important exhibitions in the world at the time.

Maja left Philadelphia soon after to be part of a notable exhibition in 1952, Sculpture of the Twentieth Century, organized by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. According to Andrew Carnduff Ritchie, Director of the Museum’s Department of Painting and Sculpture, the exhibit was intended to “give as comprehensive a view as possible of twentieth-century sculpture in all its richness and variety of expression.” The Philadelphia Museum of Art was the first venue for the Sculpture of the Twentieth Century exhibition, which then traveled to the Art Institute of Chicago and culminated at MoMA in 1953. When Maja returned to Philadelphia, the sculpture was installed by the Association on the East Terrace of the Philadelphia Museum of Art until 1992, when it was removed and placed in storage along with other nearby sculptures due to the renovation of the terrace.

Carefully Restoring and Preparing Maja

To ready the sculpture for installation in a public park, Maja required extensive conservation to restore the bronze and protect the artwork from the outdoor elements. A state-of-the-art laser treatment was performed to delicately and meticulously remove the sculpture’s streaky surface corrosion, and a special wax coating was then applied to protect the bronze from further deterioration. To develop a treatment approach, the conservator on the project first consulted other casts of Maja, which can be found at the Franklin D. Murphy Sculpture Garden on the UCLA campus; outside Kunsthalle Emden in Germany; at the Kunst Museum Winterthur in Switzerland; and in other collections. More about the conservation ››

Marcks: Bauhaus Teacher Targeted by Nazis

Gerhard Marcks (1889-1981) was a German sculptor, printmaker, and designer who helped revive the art of sculpture in Germany in the early 20th century. Marcks held teaching positions at the Bauhaus (1919-1925) and the Halle School of Arts and Crafts (1925-1933). In 1933, Nazis dismissed Marcks from his teaching post after he tried to protect a Jewish student from persecution and protested when his Jewish colleagues were fired. The Bauhaus – a school of art and design whose members wanted to shape the future of Germany both politically and artistically – was seen as a threat to the Nazi regime. More on Gerhard Marcks ››

Labeled “Degenerate Artist” by Nazis

This installation of Maja calls attention to the resolve of artists working under duress or persecution. In 1937, the Nazi party held two art exhibitions in Munich – The Great German Art Exhibition, which was meant to show works that Adolf Hitler approved of, and The Degenerate Art Exhibition, which was meant to teach the public about the “art of decay.” Hundreds of works that were seen as too modern, expressionistic, or by Jewish artists were included in the latter exhibition, including Gerhard Marcks’ own sculptures. Although Marcks was creating figurative work, it was considered by the Nazis to be too expressive, disproportionate, and not about a German ideal. Marcks was then barred from exhibiting or selling his sculptures, and a number of his artworks were subsequently confiscated, melted down, and repurposed for war materials.

Marcks later relocated his studio to Berlin, where he continued to create new sculptures. In November 1943, a bomb destroyed his home and many of his sculptures were left in pieces, but Maja miraculously survived. Walter Gropius, Bauhaus founder, said of his colleague and friend, “…his human qualities, guided him through hell and high water when a bomb destroyed his house, his studio, and his work, and when the Nazis called him degenerate, forbidding him to work. His spirit, though, could not be crushed and guided him to today’s broad recognition.”

Voices heard in the Museum Without Walls: AUDIO program: Dr. Arie Hartog is Director and former Curator of the Gerhard Marcks Haus in Bremen, Germany, which houses a substantial collection of works by artist Gerhard Marcks. His research focus is the history of 20th century sculpture. Dr. Paul B. Jaskot is Professor of Art, Art History and Visual Studies at Duke University. His scholarly work focuses on the political history of Nazi art and architecture as well as its postwar cultural impact. Patricia C. Phillips is a public art scholar, curator, art critic, and a trustee of the Association for Public Art (aPA). She is the former Chief Academic Officer and Academic Dean of Moore College of Art & Design. | Segment Producer: Alex Lewis | Videography: Greenhouse Media

Museum Without Walls: AUDIO is the Association for Public Art’s award-winning audio program for Philadelphia’s outdoor sculpture. Available for free by phone, mobile app, or online, the program features more than 150 voices from all walks of life – artists, educators, civic leaders, historians, and those with personal connections to the artworks.

PROJECT TEAM AND PARTNERS: The Association for Public Art worked with Philadelphia Parks and Recreation, Ground Reconsidered and AIR Communities to install Gerhard Marcks’ Maja sculpture in Maja Park, the new public park on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. The development of Maja Park, designed by Ground Reconsidered, has been a private/public partnership between AIR Communities, which owns the adjacent Park Towne Place Museum District Residences, and Philadelphia Parks & Recreation, with support from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Councilman Darrell Clarke, PA Senator Larry Farnese, PA Representative Brian Sims, the Parkway Council Foundation, and The Dezzi Group, Ltd.

Partners for this sculpture installation also include Gerhard Marcks Haus, Bittenbender Construction, Adam Jenkins Conservation Services, LLC, Jeffrey Fuller Fine Arts, LTD, Atelier Fine Arts Services, Radio Producer Alex Lewis, and Greenhouse Media.

Enjoying this content?

Click here to donate and help us continue to tell the story of public art in Philadelphia.