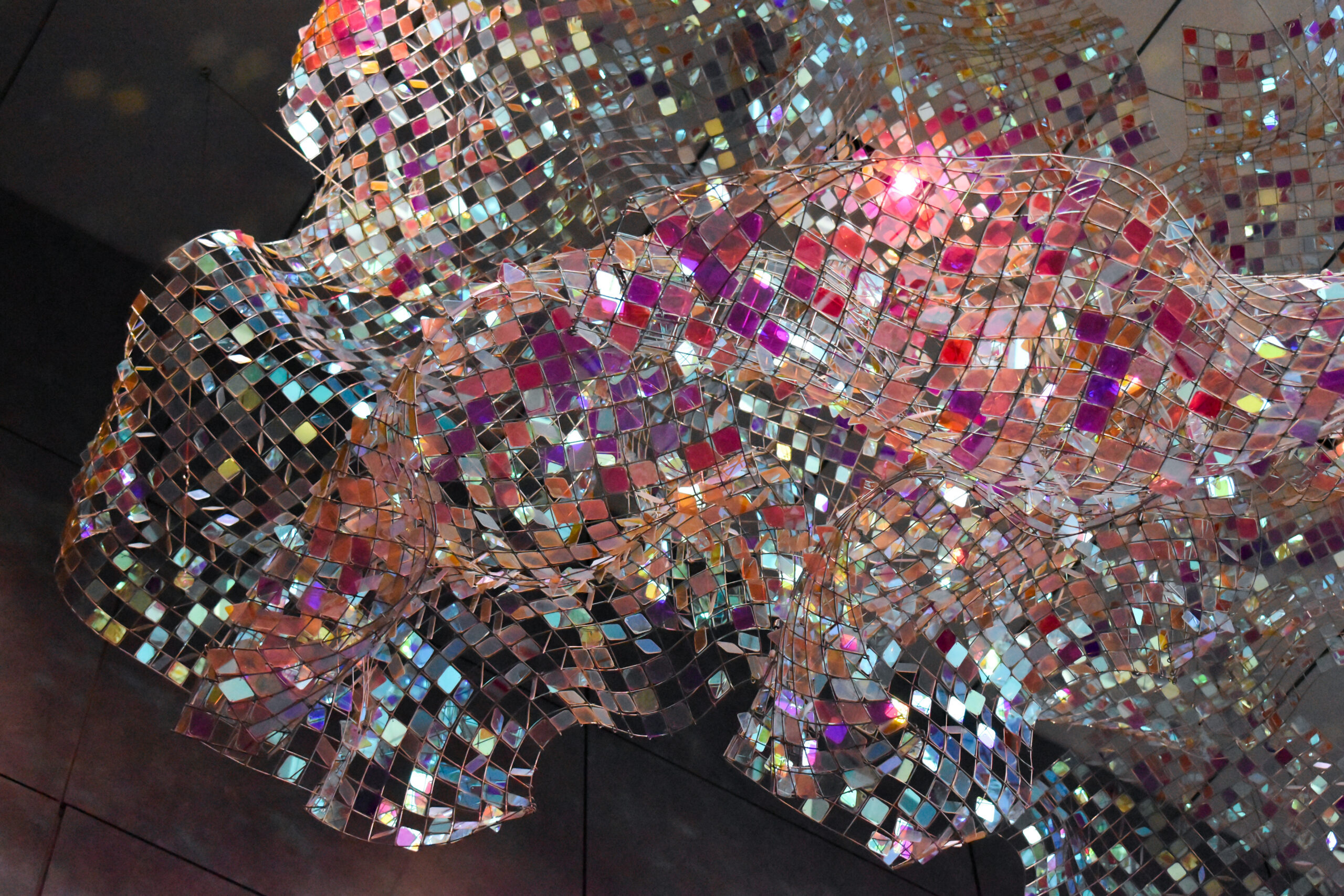

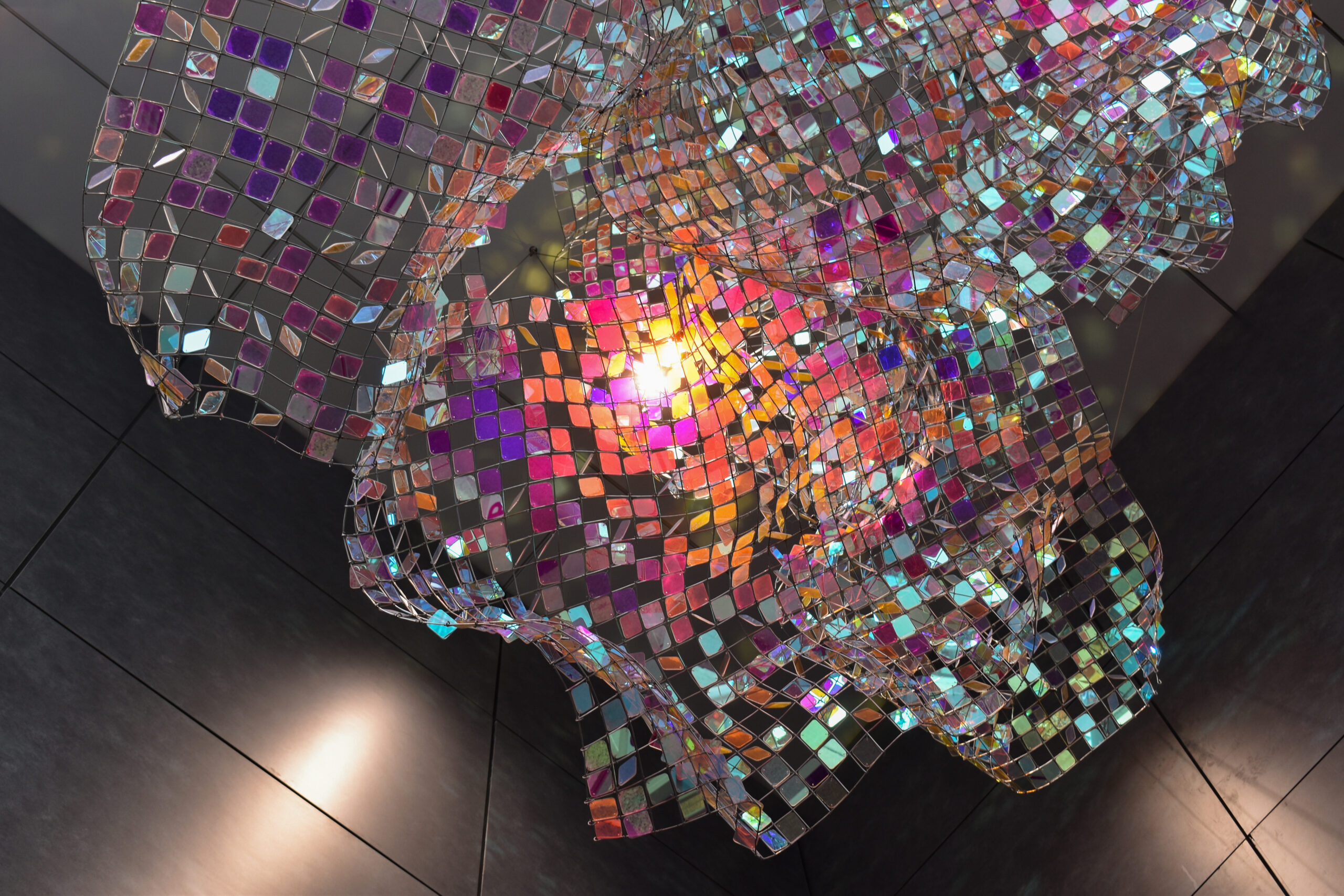

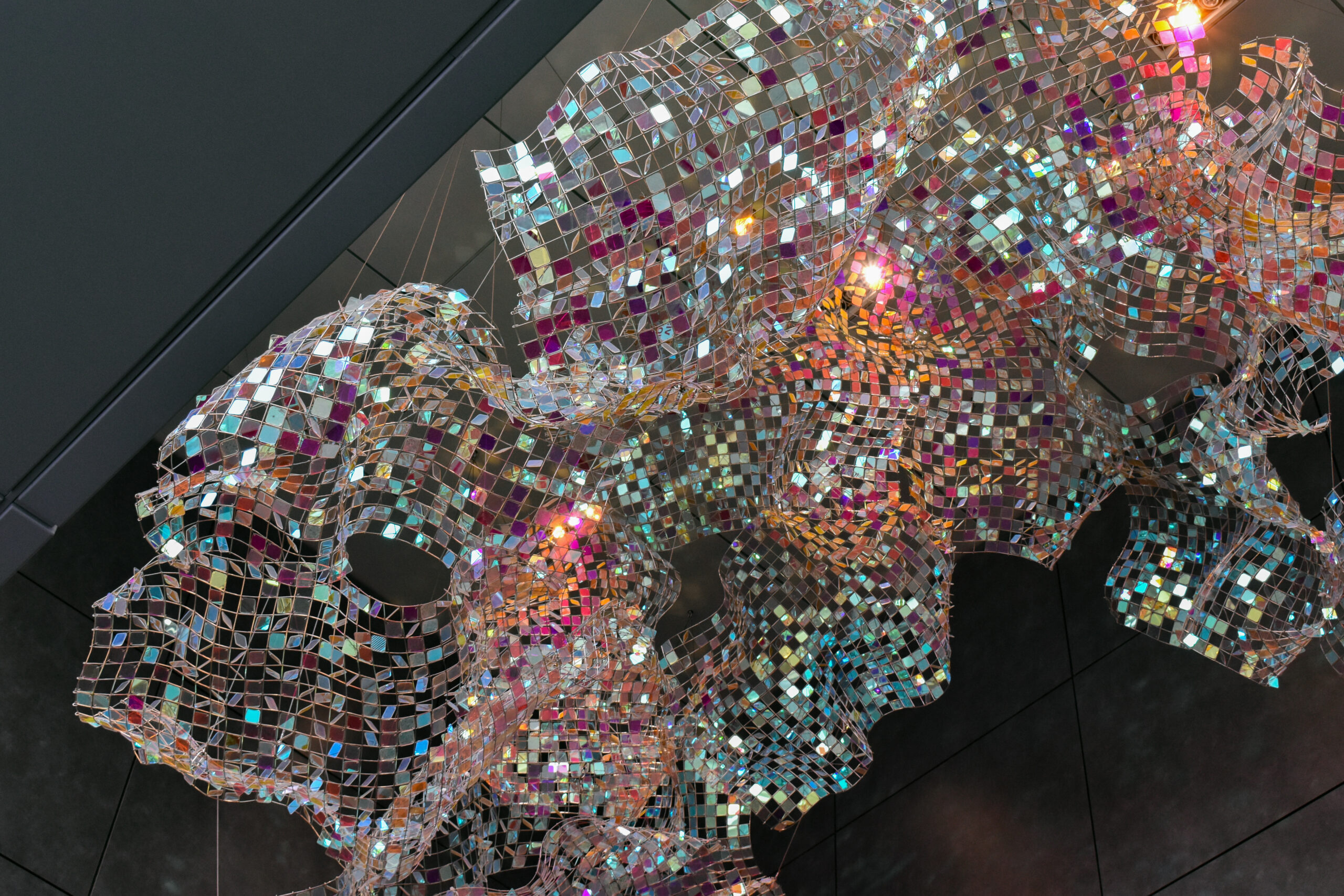

An award-winning contemporary artist known for her mesmerizing installations that blend sculpture, light, and space, Soo Sunny Park recently spoke with the Association for Public Art about her artistic inspirations, fascination with light, public art practices, and insights from teaching at Dartmouth College. The artist’s shimmering Generative Luminance sculpture at the University City Science Center is one of several public works that we’re highlighting as part of Philadelphia’s (re)FOCUS festival – a celebration of women artists.

Association for Public Art: Who are some of your biggest artistic inspirations? Women in particular?

Soo Sunny Park: Brazilian artist Lygia Clark explored the spaces between observers and artworks with geometric, woven, and biomorphic forms. From Modulated Surfaces (1957-1958) and Creatures (1960-1966) to her famous Abyss Mask (1968), she challenged the ways we ordinarily experience space and the things that inhabit it.

My early approach to sculpture was influenced by Boris Groys’ writing on the collection and preservation of artwork. He suggested that the art-making system compelled the artist to create “new” work in order to be collected. In response to the article, my early efforts (1997–2004) were ephemera that created lasting experiences via impermanent events. In that sense, the ‘non-object’ played a central role in my earlier forms, which were eventually reclaimed by nature or reprocessed into another sculpture or substance.

Since 2005, I have moved away from ephemera and expanded my engagement with the spaces between artistic categories to explore liminal states more generally: those between light and shadow, seeing and showing, artifice and nature, dwelling and elsewhere.

I try to investigate categories—sculpture and drawing, public and private, inside and outside, medium and message—by making things that locate viewers in the spaces between them.

Association for Public Art: Where did your fascination with light come from?

Soo Sunny Park: When I was young, I had an intense experience in which I noticed that I seem separate from the world, but also from my body. There’s me, over here, and the world and my body, over there. But I’m also not separate from my body, and what would the space between my body and my mind even be? This is fascinating and confusing. I think that made me interested in liminal spaces generally. I try to investigate categories—sculpture and drawing, public and private, inside and outside, medium and message—by making things that locate viewers in the spaces between them.

Light is the ultimate liminal being. It’s what allows us to see in the first place, but we don’t really notice it, the light, except under special circumstances. My goal with recent work has been making the light a structural element alongside the fencing, plexiglass, lath, and other materials that make up my installations and objects. Light is no longer just a mediator between viewers and the work, but is it part of the medium with which they engage.

Association for Public Art: Many of your pieces seem so organically shaped, like they would be impossible to reproduce. How do you decide on the shape of your installations?

Soo Sunny Park: My installations are often built out of modular forms, which I have to make at my studio, then ship to the installation site. Installation sites differ a lot! Sometimes, I need to make a scale model of the space, and the components of my work, and design the whole thing beforehand. If I don’t do that it might be impossible to install the piece in a reasonable amount of time. But other spaces are much more forgiving, and I can compose the piece on site. That lets me react to the space and the work within it in real time.

Association for Public Art: What was the experience like of being commissioned for Generative Luminance? For example: How did you work with the team to negotiate what you would do there? Were there differences of opinion and, if so, how did you resolve them?

Soo Sunny Park:As I recall, there weren’t many big disagreements associated with Generative Luminance. What stands out most is that the project was a special challenge because it involved glass tiles, not acrylic tiles. I love the look of the dichroic glass tiles, but they are a bit thinner and much more delicate than acrylic. This required rethinking some of our making practices in the studio, such as coming up with a special tool contraption for drilling each tile hole with a diamond drill bit, working with art handlers to ensure safe transport, and extra care during the installation.

For me, art is about reminding ourselves that it is always possible to ask questions, rethink boundaries, and create new things. This vision fuels my work, and I hope that my work, in turn, gives creative energy to those who interact with it.

Association for Public Art: How is conceiving of a work for the public realm different from creating other works in your practice? How do you approach the issues of longevity or “permanence” of an artwork in a public area that will inevitably change over time (both in terms of its use, audience, other stakeholders)?

Soo Sunny Park: Fundamentally, I enjoy transforming the spaces in which people live and work. My most experimental work is usually presented as temporary exhibitions in museums, but my most enduring work is the permanent installations that thousands now live with throughout the world. I am honored to touch people’s lives in this way. For me, art is about reminding ourselves that it is always possible to ask questions, rethink boundaries, and create new things. This vision fuels my work, and I hope that my work, in turn, gives creative energy to those who interact with it.

Association for Public Art: You are a professor of Studio Art at Dartmouth College. What do you see as some of the major issues of the art world? And in public art specifically?

Soo Sunny Park: People are drawn to art making because it feels like the right way for them to engage with the world. This involves expressing yourself, so becoming an artist involves a lot of self-reflection. Gender, equality, race, feminism, trans issues, worries about fascism, colonialism, and so on are definitely big topics in art making because they are big topics in the world we inhabit. In public art specifically, I have noticed an explicit intention to want works to make spaces welcoming in an inclusive fashion, which means that the art transforms the space in a way that makes people from lots of backgrounds engaged, welcome, and interested. It’s not acceptable that the price for welcoming some is excluding others, but it’s not always obvious how to do that, and different kinds of spaces present different kinds of challenges in this regard.

Association for Public Art: What do you hope to impart to your students?

Soo Sunny Park: As a sculptor teaching in various genres of visual art, my primary goal is to guide students with active, creative, and engaging assignments, to provide inspiring visual resources and reading materials, and, in a broader sense, to facilitate the skill development needed to articulate ideas visually in each chosen discipline.